If you unpacked my suitcase on my maiden voyage to the Grenadines, you would find a few somewhat modest but colorful bikinis, worn-in Havanas sandals, my Shun chef knife, smoked salts from Seattle, and butcher twine for trussing a chicken, just in case.

I was to set sail, as I had done a dozen or so other times in the past year, to cook for guests aboard. I step on to a new, unfamiliar, boat each time—a Lagoon 52, a Bavaria 51, a Leopard 44, a Juneau 53, some with a reefing system and self-tailing winches—all boating terms that sounded like gibberish when I first began the work. The inconsistencies of chartering only exasperate the many variables of travel—will I sleep on the bow or in the galley if it rains; will my propane oven work or will it go out mid-week as it often does; do I have enough wine glasses such that if three break on a big wave I have enough for dinner that night; will my fridge be cool enough so that my meat won’t sour a day after its purchased or will it freeze instead on the day it’s meant to be used for lunch? As the chef, I commit to making the best of whatever is available to buy that day. But tacked on to all these variables this time was a destination I had never been to before. I knew nothing of St. Vincent and the Grenadines before my captain, business partner, and boyfriend, said that we were headed there to take some thrill-seeking kiteboarders on a weeklong wind-hopping tour through its myriad tiny islands.

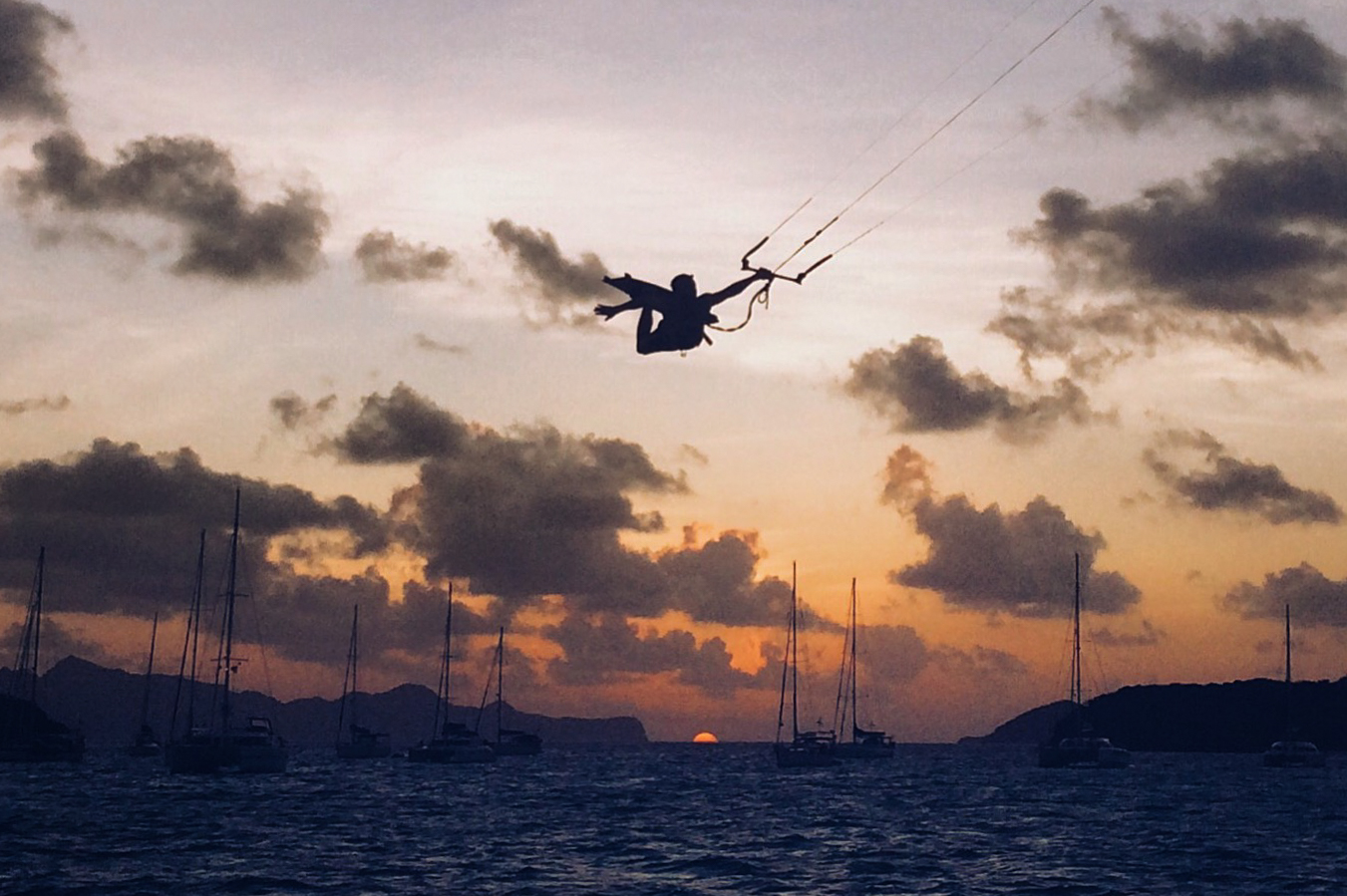

Kiteboarding has bubbled up to the surface of mainstream consciousness, having moved from its place within the perimeter of “extreme sports” to one that the kids try out on family vacation in the tropics. Don’t be fooled, though. I watched as even our seasoned kiteboarders were swept out of the protected lagoon by a strong downwind gust or forced to paddle against the current to retrieve their board. When you are harnessed to a kite four times your size that hangs two-stories above, one wrong move can plaster you against the trunk of a palm tree if you’re not careful, then warp your kite like tumbleweed in a tornado.

I am no kiteboarder. I get my thrills by walking a mile up a dusty road, off of a tip from a local named Black Boy. I came across him smoking a joint under the shade of his palm tree on Mayreau Island, and he pointed me in the direction of a village on the other side of the island selling the only pork ribs around. Rather than accept a ride, I chose to find it on my own walking under the intense heat of the midday sun. What I seek, like the kiteboarders who hired me as their guide, is to voyage into the unfamiliar.

Backtrack a few days ago before the trip started. We were walking along a dusty trail leading to a picturesque waterfall—the kind you swim under and send the picture as a postcard—when we crossed paths with a toothless farmer wearing barely-held up pants, muddy rubber boots, and a faded t-shirt. His creole was too thick to comprehend by my unpracticed white-American ears. Without prompt from us, he motioned to follow him deeper into the jungle. While many might hesitate before following an indecipherable stranger holding a machete, we nonetheless accepted his invitation, which took us to a tree hanging with ripe hibiscus-colored baseball-size fruits. I relished in the exotic taste of these tropical fruits as I ate the two, then five fruits passed my way. The skin was waxy and crisp like a pear with a white juicy interior that softened as I bit into it. Its delicate rose-like smell wafted around us in the shade of its tree. I later discovered its many names as I wandered Grenada’s Saturday market—French cashew, plumrose, Malay apple, rose apple, and others. Our fruit farmer, who had invited us to share in the plenty of his personal French cashew tree, planted a stone’s throw from his one room home, filled our backpacks to the brim. The fruit acted as a wordless welcome to these Spice Isles, filled with smells and tastes I would soon joyfully discover and pass on to my guests. The next day, I displayed his beautiful fruits in a white bowl at the entrance to the boat—an invitation to our guests as they boarded their vessel and home for the week.

Food was my currency of communication.

On the islands, grocery stores were scarce and minimal, so instead I bought all the food from someone: mahi mahi from Xavier, a local fisherman who visited my boat every other morning; soursop from Jenny who manned a fruit stand on Union Island; and lobster from Cliff who cooked it alongside his girlfriend on the sandy shores of the uninhabited Tobago Cays surrounded by a ring of coral reefs. Like a nostalgic nod to the days before giant one-stop-shop grocery stores, food here still remained an exchange not just of goods, but of information and personal history. It was a seamless part of the daily routine in the Grenadines and the backbone of social interaction.

Underneath the rainbow of umbrellas at Grenada’s Saturday market, women and men softly chatted as they hand-shelled pigeon peas into plastic bags, occasionally taking a break to coax me into buying their baby purple peppers, stalks of bananas, or clusters of nutmeg and mace and jeera (aka cumin). On the coast of Grenada at dusk, I walked past a group of twenty or more villagers as they pulled in the heavy-laden nets full of jacks fish. Their ages ranged from little kids who helped collect the squirming fish into buckets to older men and women who negotiated the communal task of pulling the rest of the net on to shore before night fell. The deal was, you help, you take home fish.

As the outsider, I yearned to be invited into the local community. To join the conversation, I’d ask about recipes. One fruit vendor who quietly sat beside his wife in their life-size doll house painted in bright Easter egg colors with a small roof awning to provide shade, jumped up excitedly as I began to feel and smell the aromatic baby pineapples hanging in their front doorway. I hadn’t intended to buy any, having brought many of the islands luscious pineapples back to the boat already. But he stepped in, asking what I did with the rinds. His eyes widened as I replied, joking with a smile that I was crazy to throw away the rind of the pineapple, when they were perfectly good added to boiling water, a little sugar, and made into homemade pineapple juice. The draw of trying something new from a local tip convinced me to buy a bunch.

At a stop in the interior hills of Grenada a young woman grilling in her repurposed oil drum told me that the secret to her family’s remarkably succulent chicken barbecue was that after they boil the chicken (before grilling it), they add the leftover water and a case of Carib beer to the sauce. Her family, in concert with the many others, dragged their makeshift barbecue to the street every Friday, turned on the reggae, and greeted friends and family with fresh juice or local rum as they informally passed through, eating whatever was cooking or just catching up. It was an open invitation.

My challenge was to acquaint myself as quickly as possible with these foreign foods, enough to create a week’s worth of luxury meals for ten hungry guests on a constantly unstable platform. I have to remain malleable and attuned to the whims of the group and the logistics of sailing, accommodating for allergies, a fluctuating daily schedule, and variables of seasickness, sunburn, and dehydration. But for my crew of kiteboarders, the practice of remaining fluid was effortless. Despite the countless unknowns and unplanned excursions -- or perhaps because of them -- our only expectation was of something we hadn’t yet experienced. We were each excited by the adventure of navigating through the unknown.

Our week was framed by the full moon. To celebrate, we congregated on the windward side of Union Island, where Jeremie Tronet, the pro-kiteboarder most famous for his “Jesus walk” trick, was hosting a full moon party complete with barbequed Lambie (the meat of the marine mollusk found in a conch shell) and rum. Dressed in black with lights running through his kite and down around his legs, Jeremie walked into the water towards a large metal basin that hovered above the saltwater flats, filled with a tower of dried palm fronds. Invisible in the darkness were the four thin nylon threads that connected him to his kite, which wafted directly above him like a patient hawk above its prey. At once, he lit a spark and the fronds erupted into a 15-foot flame. With it he sped away from the statue into a dark waters beyond. Silhouetted by the spotlight of the full moon, gaining speed, he leapt over the flame, turning the energy of the wind into an artistic performance. He waltzed with his kite over and around the flame, to and from the waters edge to a beach of growing onlookers. Once the fire had nestled into the ocean, our crew of eager kiteboarders—like giddy schoolchildren at the last bell—flocked to the water, their boards in hand and tethered to their kites like wings ready for flight. One-by-one, they tilted their kites downwind, on a race through the moonlight highway.

The wind and water shape these islands. I met Kevon, a 28-year-old fisherman in a tiny low-lit rum bar on the southern part of mainland Grenada. He was in tune with global current events—while listening to Jamaican rap music he spouting dreams of visiting Mongolia to see its animals before they became extinct. Although very much influenced by his “millennial” generation, he also remained keen on preserving his past. He sailed around the islands to sell his fish to a nearby restaurant, and in his free time raced wooden sailboats with his friends. The boats are still made right around the corner from his home, a continuation of the tradition of boat building of his Ciboney and later Carib ancestors. On our return to Grenada, we sailed alongside a small sailboat manned by three locals—older gentlemen, whose white curly beards were a stark contrast to their dark, sun-weathered faces – while their fishing net dragged behind them, the end of it marked by an almost invisible empty 5-liter water jug. Like Kevon, they practiced the old style of fishing in the Grenadines as a means to catch fish. Sometimes preservation of heritage is born out of necessity, and boating was an integral part of the daily diet. It was essential to the Grenadine’s food culture, thus allowing it to remain intact.

I was seduced by how personal the food sources were, lured by the homegrown meats, fruits, and vegetables sold in the markets or on the street. How little of outside exported food there was. There was a life to the food outside of the vertical fluorescent-lit aisles of a grocery store. What a relief from the plastic and packaging—literally and culturally—that plagues other popular tropical destinations.

If you opened my suitcase upon returning home, you would find dried shredded cassava for the cassava pone recipe from Margaret, a welcoming B&B owner tucked into Woburn Bay on Grenada I stayed with my first few nights before moving on to the boat; Curry for the fish curry recipe Kevon explained over a couple shots of rum in the dimly-lit aptly named “Hangover” bar; And Ms. Jo’s hand-rolled cocoa balls mixed with nutmeg, mace, and cinnamon—the three essentials of the Spice Isles—from Saturday’s farmer market on Grenada. All remnants of an invitation. An exchange between person and place.