Hey there.

It's been awhile. One year, two months, and a week to be exact since I wrote on this blog. I never stopped writing completely, but sharing it publicly felt too exposing. As I went through all the major life changes I've taken on over the past year, my writing got swept aside, laying patiently dormant. But I always felt guilty as if it were some small child I neglected. That's sort of how creative processes are--they go into hiding when life challenges you most, until you realize one day that a part of you has been missing. That it's been there the whole time, waiting for you to make time in your solitude to visit them again. To nourish them and be nourished by them.

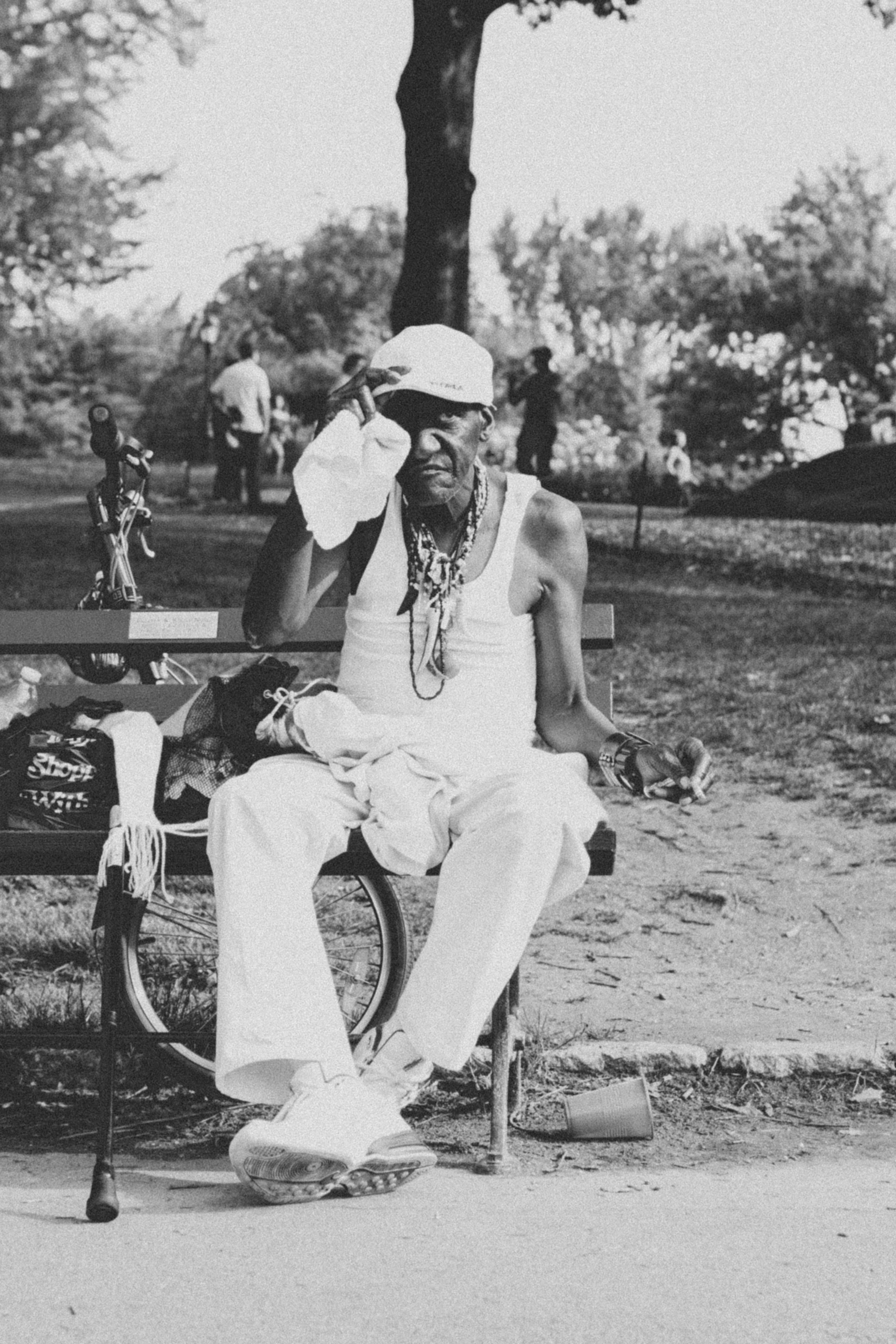

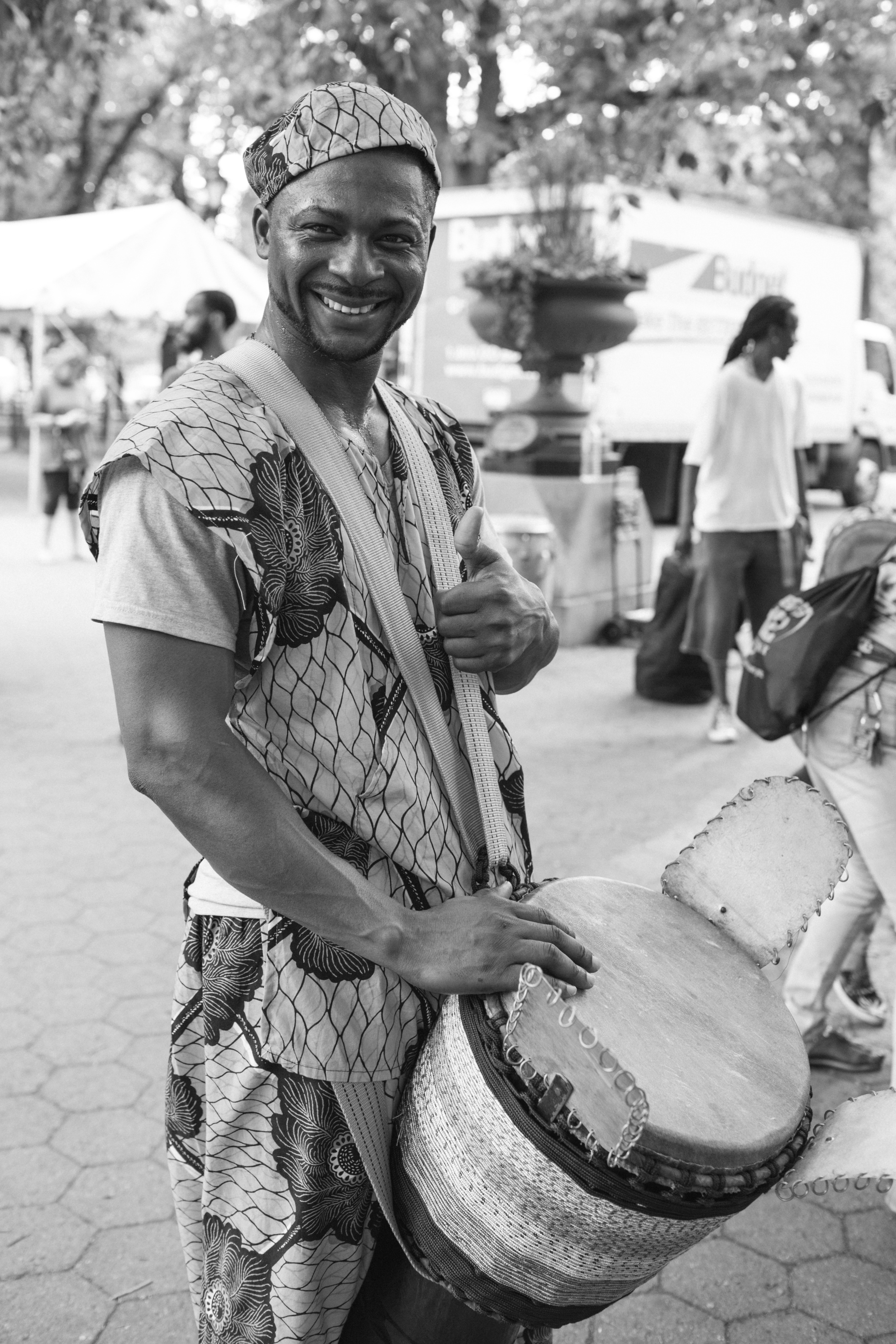

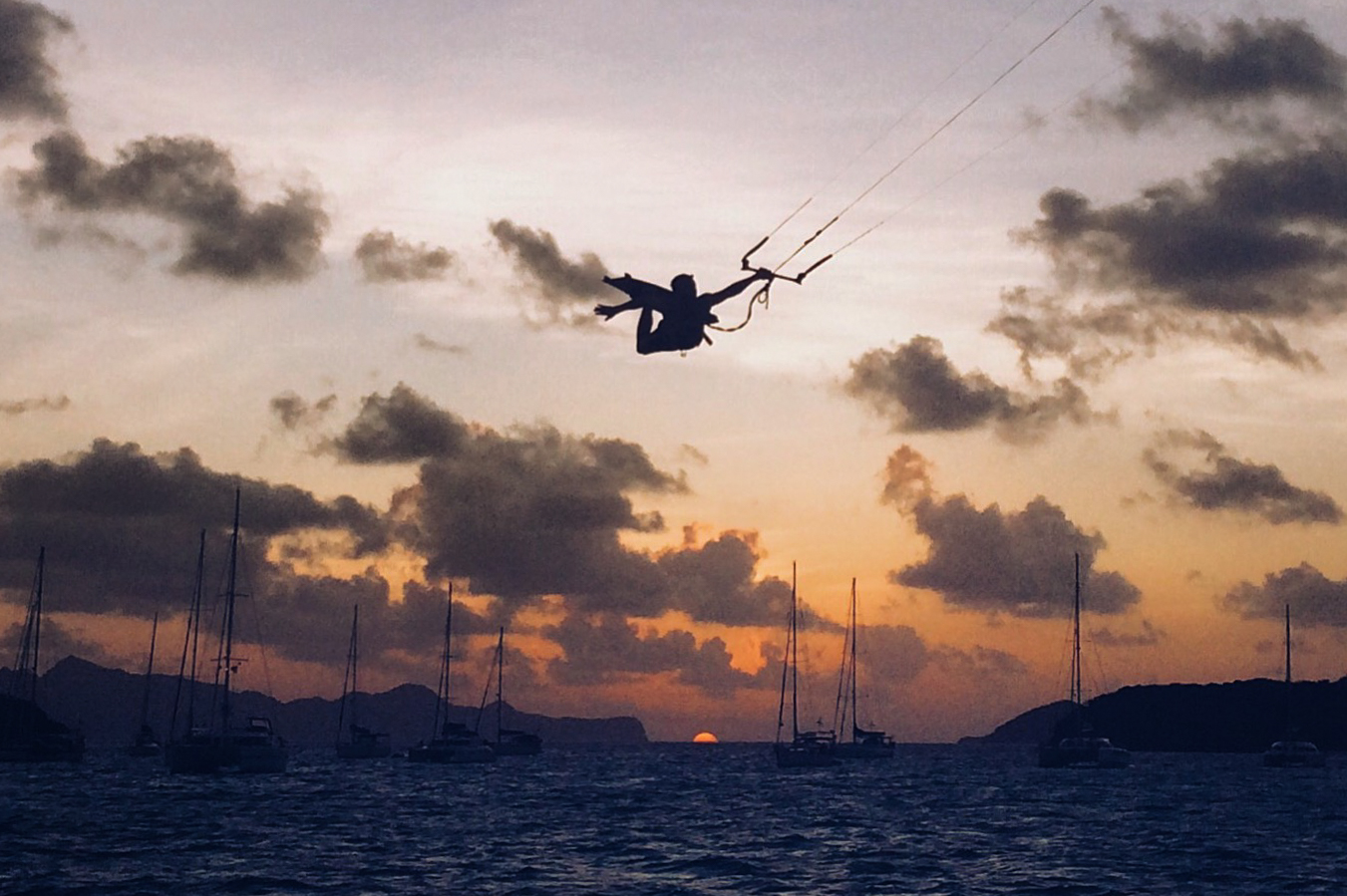

I've been surviving some big changes in my life. Walking alone for hundreds of miles. Moving to New York. Freelance. Creative work as work instead of just a side hobby. Moving to the equator. Living on a boat. Working and living with my partner. I use the word survive because it takes courage to leap into the unknown. To turn everything upside down that is comfortable and easy and to always choose the riskier path.

I changed homes so many times in the past three years I lost sense of what "home" means to me, internally and physically. A good friend recently said that home exists in the space between your heart and the people and places you love. But I struggled to find that for months and months. I learned that without that sense of home, loneliness is a deeply painful drifting, swirling feeling with no roots, no anchor (ironic metaphor, I know).

Food became a home but also a point of contention. Cooking morphed from being my creative exhibition to my crawl space. It became both a seemingly endless routine and a necessary outlet of emotions. It was a tunnel that sometimes didn't feel as if there was a light on the other side, but its also what got me out of that tunnel.

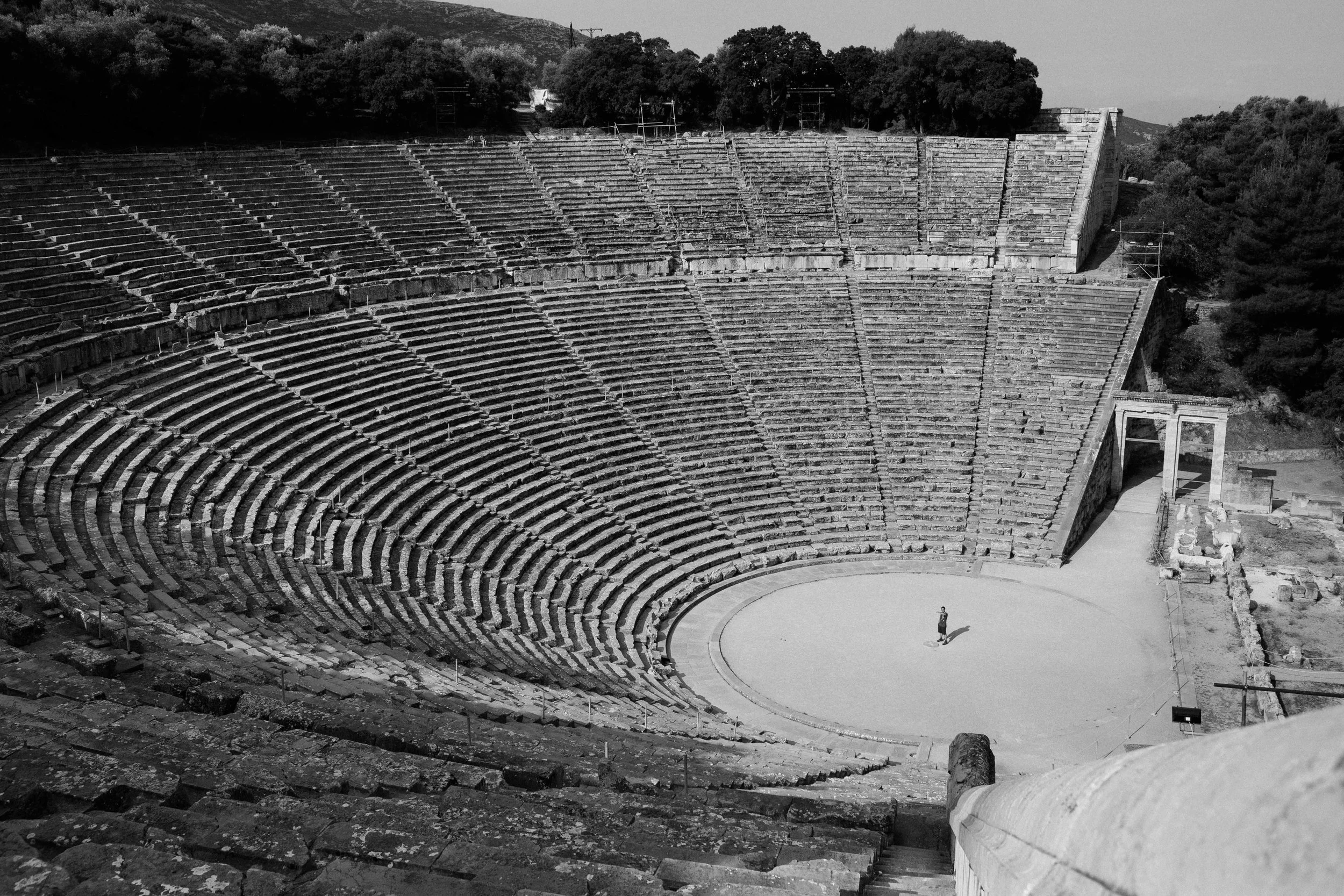

I flew back to Seattle this week, to the home I grew up in, to old friends, and family. To all things wonderfully familiar and comfortable. At first, I vowed that I would take a long break from cooking and being responsible for feeding people in general, worried that it would bring up anxieties I felt in regards to cooking professionally recently. But when an opportunity arose to wander into the backcountry of Mt Rainier with some of my dearest friends, I volunteered to plan the food. The challenge was to plan two lunches, dinner, and a breakfast easy enough for a backpacking stove, light enough for us to carry, while being delicious (because one of the best parts of backpacking is how good the food tastes when you're done). And I took the challenge, not just because I had the extra time but because I genuinely needed to reconnect with food in a new and positive way, and in turn, with my own understanding of who I am.

I've shared the menu below, not only as a how-to guide for the outdoors but because this menu represented a healing shift for me. It nourished the soul and the body. It was the center between me, my cherished friends, and the quiet wisdom of the forest. It was home.

***************

Menu

Backpacking Indian Henry's Campground, Mt. Rainier

Note: I think most people just go with a freeze-dried option from REI because it's light and easy, but for me it feels so dull to end a gorgeous grind with a poor rendition of phad thai in a bag...if it can be avoided. Instead, with a little pre-trip prep, some good seasoning options found in small bags (the same size as your REI freeze dried option), and some tricks, you can enjoy nutritious food that will become a central part of the experience instead of just a side note to the trip.

15 miles RT, 3500+ elevation gain

LUNCH: Hummus, Roasted Chicken, Basil, Spinach, Chickpea wraps

For this lunch, I made the wraps at home before heading out. Saute organic chicken breast tenders with Penzey's "Tuscan Sunset," a mixture of dried basil, oregano, red bell pepper, garlic, thyme, fennel, black pepper, and anise. Prepare a spinach wrap with hummus, the warm chicken, fresh basil, big leafy spinach, and finish with a chickpea and couscous salad (that I had on hand leftover, but could easily be replaced with any grain you have leftover--quinoa, farro, wild rice, etc.). Wrap everything together in tin foil and the three wraps fit in one ziploc bag--perfect for the top of your pack.

DINNER: Corn and Kale Fajitas with Tomatillo Salsa, Hot Whisky Apple Cider

Fajitas are a favorite backpacking meal in part because you can use whatever is on hand. Before heading out, we cut the corn off the cob, sliced the onion and peppers, and sautéed the tuscan kale and brought them in ziploc bags. Pre-washing everything allows you to save water on the trail, and pre-prep saves you time on the trail when you're already tired. Added bonus: it also reduces food waste you have to then carry out.

For seasoning, I brought a small blend of cumin and cayenne in a ziploc as well as a tomatillo and cilantro sauce made by Frontera. At Safeway, you can find their sauce in a small plastic bag, which folds up into nothing once you pour the contents out. The salsa is a blend of roasted tomatillos, cilantro, onion, and a few spices--all natural, recognizable ingredients and did not have to be refrigerated beforehand. It added a delicious kick to the vegetables. Lastly, a few flour tortillas that easily fold in the bag and some small individual sized guacamole packets I found that come in 2 oz containers, a wedge of lime, and thats it! I specifically chose not to add meat to the fajitas so as not to risk it going bad in the hot sun all day. The vegetables with the sauce were plenty of food, but for those wanting to add more protein, I found some great refried bean options in a plastic bag that just included adding water.

For a warm beverage option we poured whisky from a flask into mugs of hot apple cider using the instant mix. Warm, spicy, and sweet for a cold night.

BREAKFAST: Steel cut oats with fresh berries

Better Oats makes very good individual-packet sized instant oatmeal using steel cut oats, which had a nicer texture than your regular instant quaker rolled oats. The fresh blueberries and sliced peaches were definitely an indulgence, but add a nice crunch, and can be easily packed in a tupperware container. Then you can use the tupperware to carry trash down as a closed vessel once it's empty. For the oats, you just have to add boiling water and stir. You could always add a splash of leftover whisky from the previous evening like my family does : )

LUNCH: PB&J, Salami, Hardboiled eggs

This one is pretty straight forward! I recommend making the sandwiches before you leave so you don't have to carry the heavy jars, and hardboiling the eggs before as well. It's a nice protein and they stay fresh enough in the shell to last until the second day. I chose a pre-sliced salami that is nitrate-free and is found near the bread section, out of refrigeration.

CUSTOM GORP aka TRAILMIX

For the past few years I've always opted for making my own custom trailmix. This time I mixed chocolate turtles (clusters of pecans and caramel dipped in dark chocolate), pistachios, raw cashews, dark chocolate covered almonds, dried sour tart cherries, and pepitas (otherwise known as shelled pumpkin seeds). You can pull from the bulk section of the grocery store or buy the individual packets and mix at home. Either way, it lets you get exactly the components and ratio you love because the pre-mixed trailmix always either doesn't have enough M&Ms, too many raisins, and way too many almonds, am I right?

A few more fun backpacking tricks I've learned...

- If you are using iodine to treat your water and you can't stand the taste, add some dried apricots, apples and/or cherries to your nalgene. It'll flavor your water nicely and once they've re-plumped themselves in the water you have a nice fresh fruit treat to munch on!

- REI sells a french press/tea thermos and mug that holds two servings of ground coffee in the bottom. It's way better than instant, and you just unscrew the coffee from the bottom, pour in, add hot water, and press down in a few minutes. Then drink straight from the mug (it has a filter for any loose grounds) or pour into a friends mug. You can bring whatever gourmet coffee you love pre-ground the night before, plus your mug can additionally be used for the aforementioned whisky cider : )

- I always bring a tarp in case of bad weather but it also acts as a really nice base to set up your camp kitchen. If you take your shoes off before stepping on to it, it helps reduce any stray dirt or needles from getting into your food and water and makes clean up after a meal easy (and the campsite clean for the animals).

- Envy apples are by far my favorite apples to bring. They're crisp, sweet, and so aromatic. I can only find them in select grocery stores in Seattle but if you do see them, get them. They're fairly big and keep well in the heat.

I hope this inspires you to go out and explore--I always feel a profound presence in the Pacific Northwest mountains. The weather is beautiful, the wildflowers are in full glorious bloom, and the snow has melted into some wonderful refreshingly cold glacier-fed pools to jump in after a hot and dusty hike!