I will remember Greece first and foremost by its cheese. Feta was ubiquitous, and in the Saronic Gulf Islands in particular, it was almost exclusively made of sheep cheese. (This was a win for me, being lactose-intolerant to cow milk.) There was a wider range of styles of feta than we're used to in the United States —from fresh and creamy that sprinkled like chèvre, to harder, earthier kinds served as a solid block atop a salad. Greece has 19 registered cheeses that fall under the DOP or PDO label--Protected Designation of Origin in English--signifying cheeses grown and produced in the local region they traditionally come from. This regulation protects the cultural reputation of the cheese (and other food products across the EU) and of its producers. In that way, from how the sheep or goats are raised to how the cheese is cured or brined, generations of history and culture are preserved in each bite of cheese.

Equally emblazoned in my mind were the colorful hues of Greece. It is a country of blue—from the brightly painted blue shuttered houses, to the sapphire blue water, the dusty evening sky, and the distant peaks that jut out from the horizon. The fluoride-white houses illuminated the sage green olive trees and the camel-colored wheat fields that terraced into the ocean below.

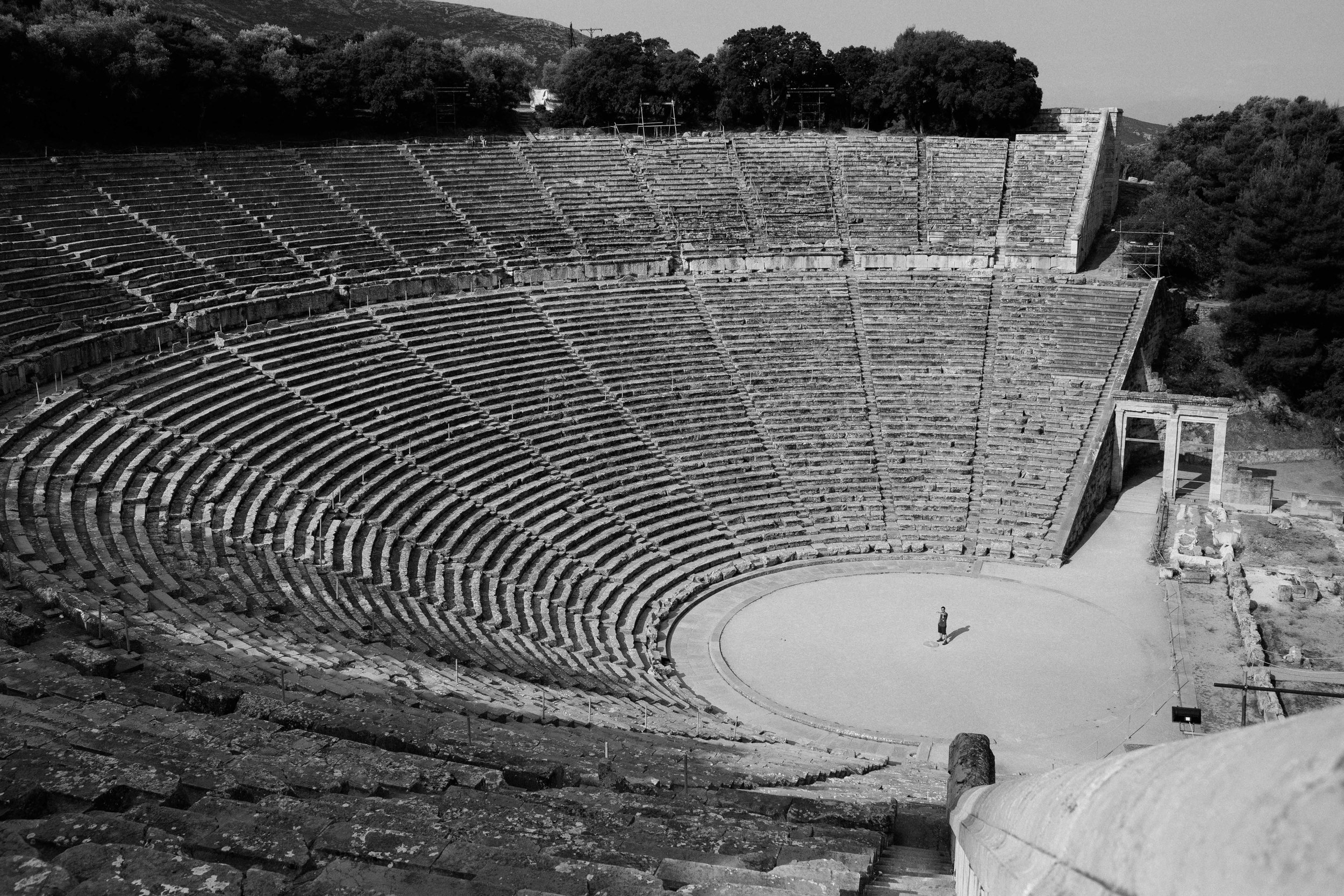

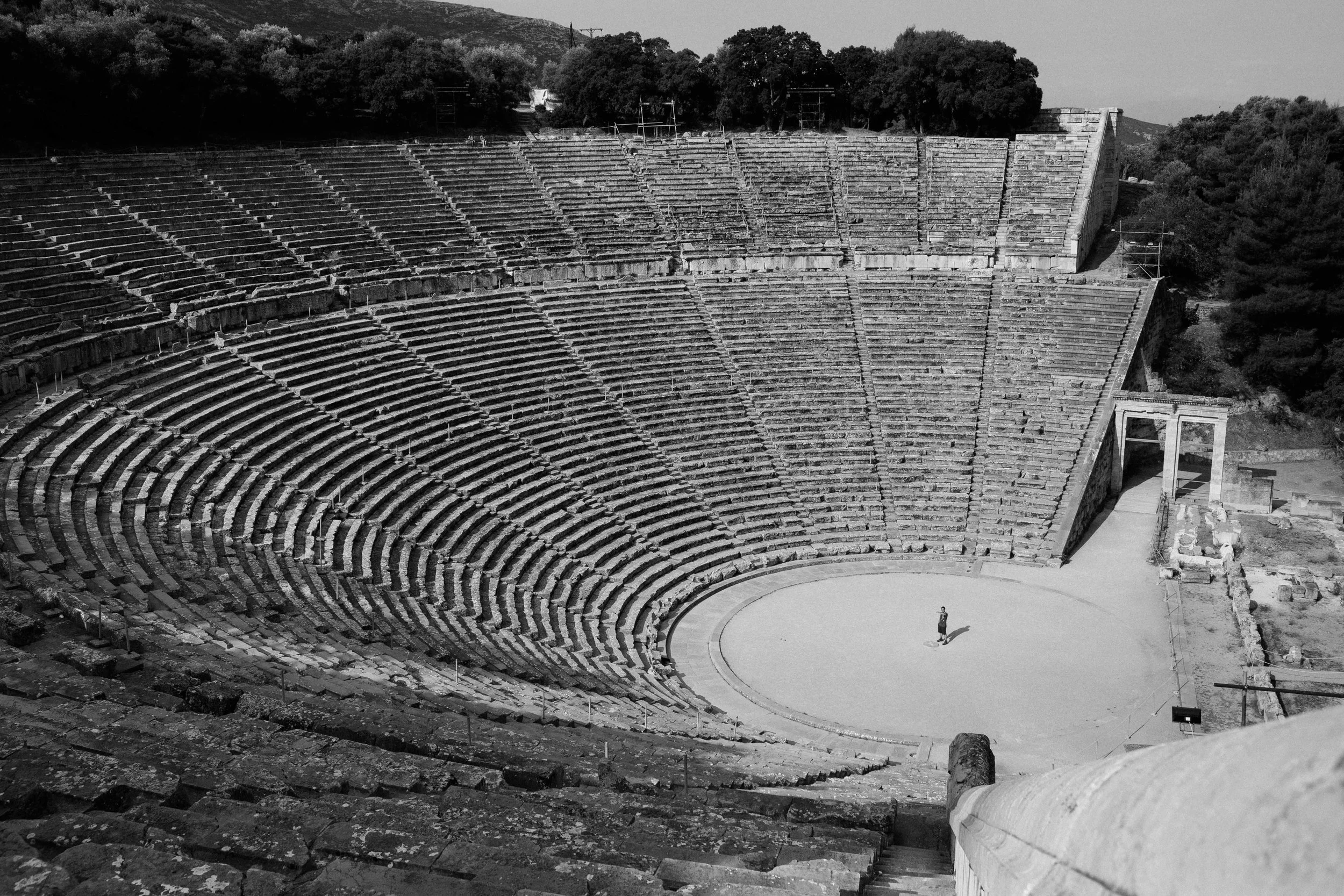

From artifact to architecture, history in Greece is woven into its surroundings. Tucked into Aegina island is the small town of Messagros, where a famous potter--the last of his kind--still practices an ancient style of pottery. Nektarios Garis, who carries on the traditions of his ancestors, still collects clay from claybeds around the island and fires his pottery in a wood-fired kiln fueled by fallen pine branches from around his home. On Andros, a beautiful little island in the north of the Cyclades (that is uniquely devoid of the common Greek crowd of tourists), old hand-stacked rock walls parcel out land along the steep cliffs. They seemed unused in current day, and more stand as a memory of ancient civilizations that date back further than I can even imagine. There is a similar feeling of awe, both from afar and close up, as you enter the ruins of the "Sacred Triangle" -- the Acropolis, the Temple of Poseidon, and the Temple of Aphaia--all of which were built by the early Minoan people (early Greek settlers) in the 5th century BC.

It seemed there were three main simple joys to life in the Greek islands: family, religion, and fish (nearly every inlet, hill, and island had a small one-room church on it). Fishing was a hobby and a profession. One taxi driver told me that his retirement plan was to fish everyday. Fisherman enter the ports in the morning on islands like Hydra, selling fish directly out of their iceboxes to locals (and throwing the scraps to the eager harem of cats awaiting their turn). Men and children idly walked the docks at night with a small cooler and a hand-reeled hook, waiting for the night squid to reveal themselves.

What Greece gave me, and more specifically the Saronic Gulf Islands, was an opportunity to play with local ingredients in a creative way. As a chef on chartered sailboats, I got the opportunity to act on a food fantasy I’d had about provisioning directly from the local fisherman and the fruit and vegetable vendors, discussing recipe ideas like “Bake this one in fresh tomatoes”, or “Fry this one lightly with oil.” I got tips from the old woman at the dried fruit and coffee shop I loved on Aegina for her fassolatha recipe. On Porros, I was recommended the right cut of lamb for kleftiko, and on Spetses, step-by-step directions on how to make the famous frothy Greek coffee, frappe. I was inspired by the different personalities on each island--from the food to the people--and that context got built into each dish.

After traveling through the Greek islands and meeting the people on them, what struck me was that beyond their enthusiasm to share their food knowledge, it was their connection to their food that stood out to me. Their food came not just from an ocean but the ocean right outside their doorstep. One restaurateur in Porros told me that fish, like produce, varied by its season here. Restaurants won’t serve a fish out of season, nor will the same fish appear year-round. Instead, you eat only the fish that can be caught that morning. At restaurants, it was common practice to be welcomed back into the kitchen or the icebox where the server would introduce you to the fish that was being served that night, allowing you to choose by its appearance and size. Throughout the meal, servers would beam with pride when they asked “Did you like that? Have you tried this? My mother made that!” Their eagerness to share, their enthusiasm for what they were serving, their pride—it seemed to me a way of outward cultural expression through food. But it goes beyond just food as cultural identity. It’s a direct invitation to outsiders—“Come taste Greece,” they’re saying. Come learn who we are through our food.